Audemars Piguet Royal Oak – A Radical Beginning

When the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak appeared in 1972, it was more than just a new model in the brand’s catalogue. It was a turning point for Swiss watchmaking at a moment of existential uncertainty. The Royal Oak’s octagonal bezel, exposed screws, integrated bracelet and industrial feel created a new visual language for the wristwatch. To understand why the Royal Oak became so significant, it is necessary to step back into the climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the foundations of Swiss mechanical watchmaking were under pressure from technological, economic, and cultural forces.

Audemars Piguet had been founded in 1875 in the Vallée de Joux by Jules Louis Audemars and Edward Auguste Piguet. For nearly a century, the company had maintained a reputation as one of the trinity of Swiss haute horlogerie brands, alongside Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin. Its speciality was complicated watchmaking, producing perpetual calendars, minute repeaters and tourbillons in small numbers. These were made in traditional precious metals and worn by a conservative clientele who saw mechanical watches as discreet markers of refinement. By the 1960s, however, the landscape was shifting.

The Quartz Crisis was just beginning. In 1969, Seiko unveiled the Astron, the world’s first quartz wristwatch. The accuracy, convenience, and lower cost of quartz movements posed an existential threat to traditional manufacturers. At the same time, fashion and culture were changing. The younger post-war generation had less interest in conservative gold dress watches. They were drawn to larger, bolder designs and wanted objects that reflected a more casual, outwardly affluent lifestyle. The economic mood was also shifting. Recessions in the early 1970s, along with the oil crisis, reduced demand for traditional luxury goods.

Audemars Piguet’s managing director, Georges Golay, realised that a new approach was required. In 1971, on the eve of the Basel fair, he reached out to the freelance designer Gérald Genta with an urgent request. The Italian market, always a key audience for avant-garde design, was asking for a watch that was sporty, innovative, and completely unlike anything then on the market. Genta was given only a single night to produce the design. He drew inspiration from a diving helmet with its visible bolts, sketching an octagonal bezel secured by eight screws, mounted on a sharply faceted case with an integrated bracelet.

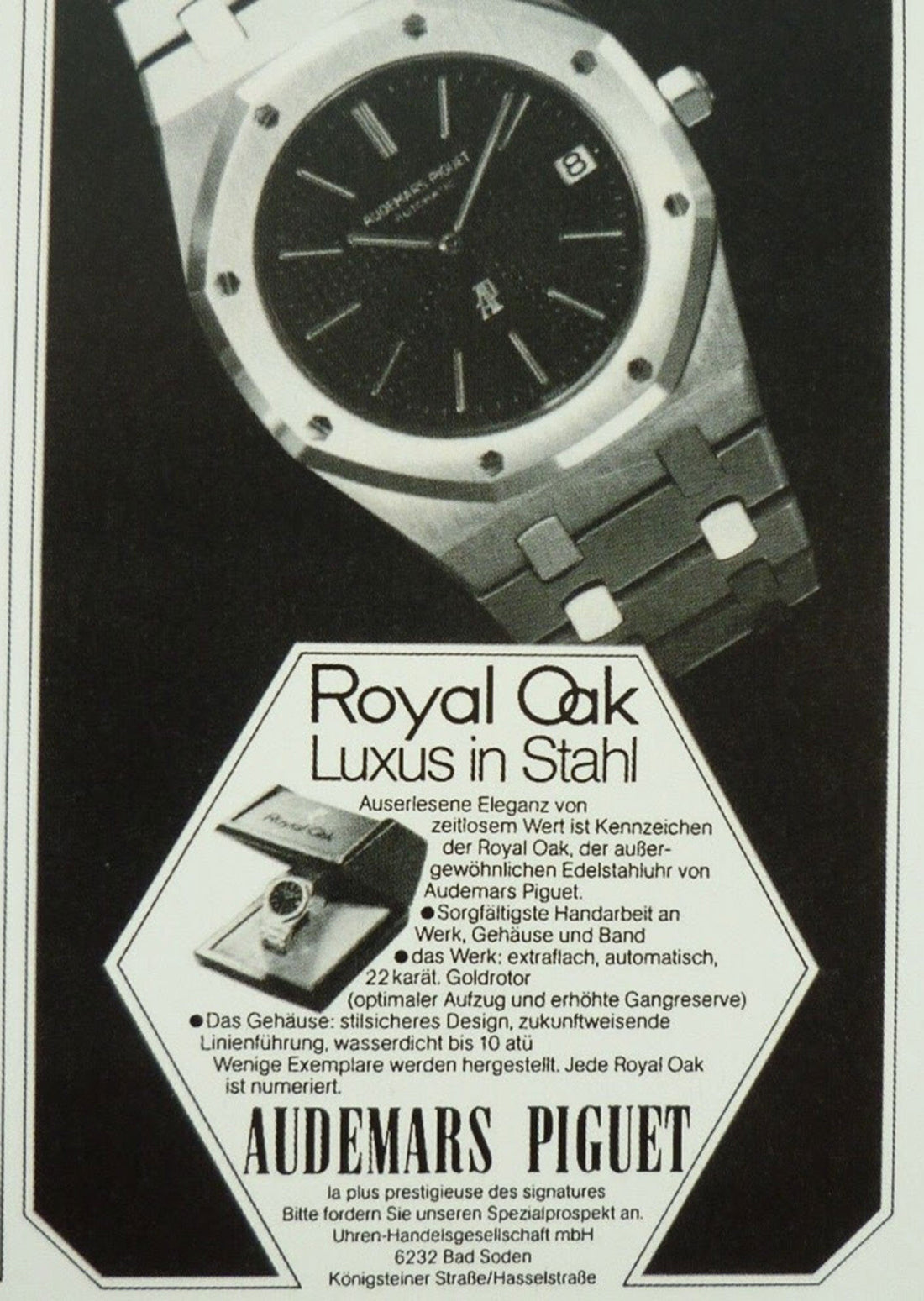

When the Royal Oak reference 5402 was presented in 1972, it was unlike anything else in the luxury segment. The watch was made not in gold or platinum, but in stainless steel. At 39 millimetres in diameter, it was large for its time, so much so that it soon gained the nickname “Jumbo.” The thickness was kept to a mere seven millimetres thanks to the ultra-thin calibre 2121 inside, an automatic movement derived from Jaeger-LeCoultre’s calibre 920, renowned for its slim profile and high performance. The dial was another departure. Rather than a plain surface, it carried a blue “Petite Tapisserie” guilloché pattern created by Stern Frères. This combination of textures, facets and colour was radical in 1972.

The price was equally radical. The Royal Oak retailed for 3,650 Swiss francs, more expensive than many solid gold dress watches of the era. The press labelled it “the world’s most expensive steel watch.” Reception at first was muted, and some dealers questioned whether the idea of a luxury watch in steel could ever succeed. But in Italy and eventually in other markets, the boldness of the design began to resonate. The watch offered the quality of haute horlogerie in a package that matched a more modern lifestyle. It was a tool-like object elevated through finishing, proportion and detail.

The early production run of the Royal Oak was modest. The A-series of the reference 5402 was limited to around two thousand pieces. These early examples are now prized by collectors for their originality and historical importance. Over time, as Audemars Piguet continued to produce the 5402 in subsequent B, C and D series, the Royal Oak gradually shifted from curiosity to cult object. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, it had achieved the status of an icon.

The Royal Oak’s creation cannot be separated from Gérald Genta’s other work. In 1976, he designed the Nautilus for Patek Philippe, another stainless steel luxury sports watch with integrated bracelet. In 1977, Vacheron Constantin released the 222, designed by Jörg Hysek, which followed the same formula. These three watches together defined a new category: the luxury sports watch. Before the Royal Oak, a sports watch meant a Rolex Submariner or Omega Speedmaster—robust tools designed for diving or space. The Royal Oak redefined the idea by blending robustness with high finishing and exclusivity. It was not intended to be a deep-sea instrument but a statement of taste.

The choice of stainless steel was crucial. Steel had long been used in tool watches but was rarely the metal of choice for haute horlogerie. By taking a material associated with utility and elevating it through extraordinary finishing—satin brushing, mirror-polished bevels, and tight tolerances—Audemars Piguet challenged assumptions about what constituted luxury. The Royal Oak was not precious because of its material, but because of the craft and design that went into it.

During the 1980s, the Royal Oak line expanded. Audemars Piguet introduced smaller versions, as well as high complications housed within the same case design. The perpetual calendar Royal Oak was particularly significant, showing that the model was not limited to time-only execution. This merging of sportiness with complications reinforced Audemars Piguet’s identity as both innovative and rooted in tradition.

In 1993, the Royal Oak Offshore was introduced, designed by Emmanuel Gueit. At 42 millimetres and with a far more robust profile, the Offshore pushed the concept further, adding rubber gaskets and a more muscular stance. Initially divisive, it eventually won over a younger audience, becoming a significant part of the Royal Oak story in its own right.

Across the decades, the Royal Oak has been produced in numerous materials—yellow and rose gold, platinum, titanium, and ceramic—yet the essential DNA remains constant: the octagonal bezel with exposed screws, the integrated bracelet, and the tapisserie dial. The dimensions may shift, the complications may vary, but the watch is always immediately recognisable as a Royal Oak.

The movement inside has also evolved. The original calibre 2121 was used in the “Jumbo” for decades, admired for its thinness and reliability. In 2022, for the fiftieth anniversary of the Royal Oak, Audemars Piguet introduced the reference 16202, powered by the new calibre 7121. This movement offers greater efficiency, longer power reserve, and modern features while preserving the slim profile that defined the original. The anniversary also underlined the enduring relevance of the Royal Oak, five decades after its controversial debut.

The historical significance of the Royal Oak extends beyond Audemars Piguet. Its success proved that Swiss mechanical watchmaking could reinvent itself at a time when quartz threatened to make it obsolete. By creating a watch that was not just a timekeeping instrument but a design object and a cultural statement, Audemars Piguet carved out a new niche. Other brands followed, but the Royal Oak was first, and it remains the benchmark.

For collectors today, the earliest A-series 5402s are the most sought after, prized for their originality and connection to the 1972 launch. Later references, particularly those with complications, demonstrate the flexibility of the design. The Royal Oak Offshore appeals to a different audience, often drawn to larger, bolder statements. The entire lineage reflects how one daring design reshaped an industry.

The cultural impact has been equally strong. The Royal Oak has appeared on the wrists of athletes, musicians and actors, cementing its place not only in horology but in broader popular culture. Yet beyond celebrity association, its importance lies in what it symbolises: the willingness of a traditional maison to innovate radically in response to crisis. Without that risk, Audemars Piguet might not have survived the 1970s as a leading name in watchmaking.

Today, when discussing luxury sports watches, the Royal Oak is invariably the starting point. Its influence can be seen across the industry, from high-end competitors to more accessible interpretations by younger brands. What began as a risky experiment in 1972 has become a pillar of modern horology.

The Royal Oak’s story is ultimately about boldness. At a time when most companies played safe, Audemars Piguet chose to embrace risk by presenting a steel watch priced higher than gold, with a design that broke every convention. That decision redefined the brand and reshaped the industry. The Royal Oak has remained relevant for more than fifty years because it was never about trend. It was about pushing boundaries, and in doing so, it created a new standard.