The Charles Vermot Story

The Man Who Saved the El Primero

Swiss Watchmaking in the Mid-20th Century

In the decades after the Second World War, Switzerland was the dominant force in global watchmaking. The country produced over half the world’s watches by value, and its brands enjoyed reputations built on precision, durability, and craftsmanship. Towns like Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds were watchmaking hubs, home to both small artisan workshops and large integrated manufacturers. The Swiss controlled the supply of high-grade movements to much of the world, and their mechanical technology was considered unmatched.

This era saw continuous refinement of mechanical calibres. Improvements came in the form of better shock protection systems, advances in lubrication, tighter manufacturing tolerances, and innovations in waterproof cases. Chronographs — wristwatches with stopwatch functions — were in steady demand, used by pilots, engineers, and sports professionals. By the 1960s, a few forward-looking manufacturers began working on an important next step: the automatic chronograph, a wristwatch that combined chronograph capability with the convenience of self-winding.

Zenith’s Rise and the El Primero Project

Founded in 1865 by Georges Favre-Jacot, Zenith was one of the first Swiss brands to bring all stages of watch production under one roof. This allowed the company to control quality and innovate quickly, without relying on third-party movement suppliers. Over the years, Zenith won numerous observatory chronometry competitions, cementing its reputation for accuracy.

In 1962, Zenith began work on a project to create what it aimed to be the world’s first fully integrated automatic chronograph. Rather than adapting an existing manual chronograph with an added automatic module, Zenith’s engineers designed the movement from scratch with both functions in mind. The challenge was formidable: an automatic winding system adds thickness and complexity, and integrating it with a high-grade chronograph without compromising precision required careful engineering.

The result was unveiled in January 1969: the El Primero (“The First” in Spanish). The movement operated at a high frequency of 36,000 vibrations per hour, allowing it to measure elapsed times down to one-tenth of a second. It used a column-wheel mechanism for smooth chronograph operation and had an integrated architecture that kept it relatively slim for such a complex calibre. The El Primero was instantly recognised as a milestone in watchmaking.

The Quartz Crisis and Zenith’s Corporate Shift

Later that same year, Seiko launched the Astron — the first commercial quartz wristwatch. Its arrival would trigger one of the most disruptive periods in Swiss watch history: the Quartz Crisis. Quartz movements were accurate to within seconds per month, inexpensive to produce at scale, and required minimal maintenance.

The impact was swift and severe. By the mid-1970s, Swiss watch exports had collapsed, and mechanical watch sales were in freefall. Many brands merged, closed, or shifted entirely to quartz production to survive.

Zenith had been acquired in 1971 by the American electronics firm Zenith Radio Corporation. The new management viewed mechanical chronographs as outdated products with no commercial future. In 1975, they issued a directive: halt all production of the El Primero, dismantle the assembly lines, scrap the specialist tools, and destroy the technical documentation. The intention was to devote resources exclusively to quartz watches.

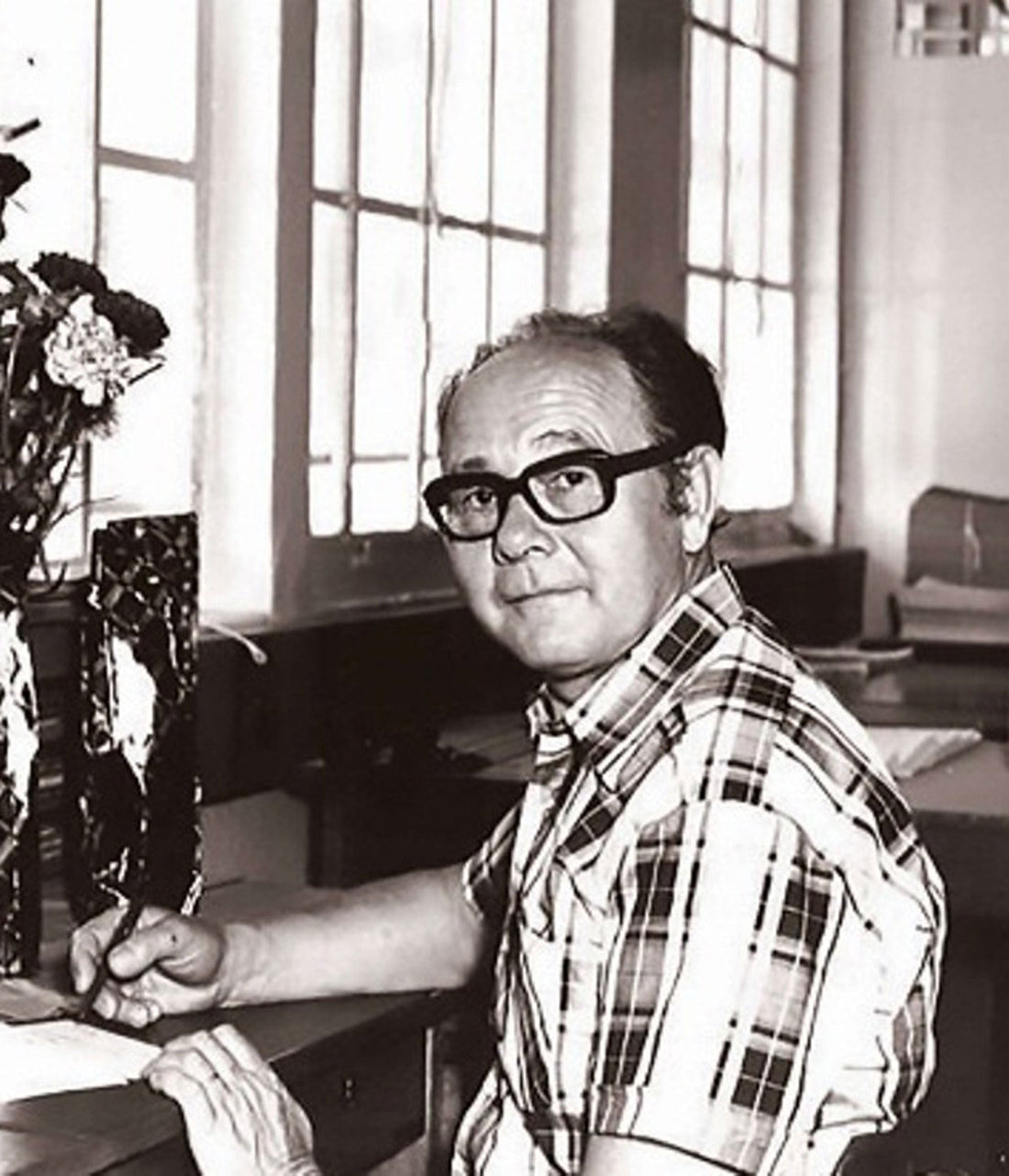

Charles Vermot’s Defiance

One of the watchmakers who received that order was Charles Vermot, a senior figure at Zenith who had worked extensively on the El Primero. Vermot understood the magnitude of what was being asked — not just the end of production, but the erasure of the technical knowledge and physical capability needed to ever produce the movement again.

To Vermot, the El Primero represented the peak of Zenith’s mechanical expertise. He believed that quartz would not be the only future, and that one day the demand for fine mechanical watches would return. Acting in secret, he began to remove the machinery, tools, and parts inventory associated with the El Primero from the production floor.

Over evenings and weekends, Vermot methodically catalogued each specialised jig, press, gear cutter, and cam, labelling them so they could be reinstated in the correct place on the assembly line. He gathered every set of technical drawings, tolerances, and assembly notes — documents that captured the practical knowledge of the workforce as well as the theoretical specifications.

He stored it all in a locked attic space in the Zenith factory in Le Locle. The attic became, in effect, a time capsule of the El Primero’s entire manufacturing capability. Vermot told almost no one what he was doing; if management had discovered his actions, he risked losing his job.

A Decade in the Attic

For the next nine years, the attic remained untouched. Zenith produced quartz watches and a small number of simple mechanical models, but the El Primero was absent from its catalogue. Across the industry, other brands were dismantling or selling off their mechanical tooling, often for scrap value. Knowledge that had been built over generations was being lost as skilled workers retired or left the trade.

Vermot continued his work at Zenith, keeping his secret. He could not have known exactly when — or if — his precaution would prove useful. But he was convinced that the era of fine mechanical chronographs would return.

The Mechanical Revival

By the early 1980s, signs of a mechanical watch renaissance were beginning to appear. Luxury consumers started to value mechanical watches for their craftsmanship, heritage, and artistry — qualities quartz could not replicate. Brands like Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and Rolex had never fully abandoned mechanical watchmaking, and they now found themselves in a stronger position as demand grew.

At Zenith, the idea of restarting mechanical chronograph production began to be discussed. The El Primero was the obvious candidate, but there was a problem: management believed the capability to make it had been destroyed.

Opening the Attic

It was at this moment that Charles Vermot revealed his secret. He told management that the tools, machines, and plans for the El Primero still existed — safely stored in the attic. When the boxes were opened, everything was there: the specialist tooling, the complete technical drawings, the labelled parts, all in the order they would need to go back into production.

Because of this, Zenith could restart El Primero production without having to redevelop the movement from scratch, saving years of work and enormous expense. In 1984, the El Primero returned, as precise and reliable as it had been in 1969.

The Rolex Connection

While Zenith reintroduced the El Primero into its own watches, word of its availability spread. In the late 1980s, Rolex was preparing to update the Cosmograph Daytona with an automatic movement. Developing one in-house would take years, so the brand looked for a proven calibre to adapt. The El Primero was chosen for its integrated design, chronometer potential, and reliability. Rolex modified it extensively — reducing the beat rate, removing the date function, and replacing over half its components — to create the calibre 4030, used in the so-called “Zenith Daytonas” from 1988 to 2000.

This side story illustrates how Vermot’s decision affected not just Zenith, but one of the most recognisable sports chronographs in the world.

Legacy and Significance

Charles Vermot retired knowing that his quiet defiance had preserved one of the most important movements in Swiss watchmaking. The El Primero remains in production today, powering both modern designs and heritage reissues. It continues to beat at its signature high frequency, a living link to the innovation of 1969.

Vermot’s actions are remembered as one of the defining acts of foresight in the industry. In an era when the prevailing wisdom declared mechanical chronographs obsolete, he safeguarded the means to produce one of the greatest examples ever made.

Final Thoughts

The Charles Vermot story is a reminder that Swiss watchmaking history is not shaped solely by corporate strategy or market forces, but by individuals with the conviction to act when others will not. In preserving the El Primero, Vermot ensured that a chapter of horological excellence would not be erased. His decision allowed Zenith to revive its most famous calibre, helped Rolex modernise the Daytona, and preserved a standard of mechanical chronograph design that still resonates today.

Without him, the El Primero would almost certainly have been lost, and the intertwined history of Zenith and other brands would look very different. In an industry where precision is everything, Vermot’s timing could not have been better.